1. Squash and Stretch

If an object moves, its movement shows the rigidity of the object. Most objects in the physical world have little versatility, such as furniture, but most organic objects have some degree of flexibility in their shape. Also squash and stretch is useful in animating dialogue and doing facial expressions. This is used in all types of character animation, from a bouncing ball to a person walking's body weight.

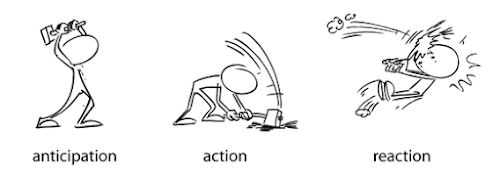

2. Anticipation

An Action takes place in three parts: the action planning, the action itself, and the action ending. Planning is the planning for the practice. Anticipation is an effective tool to indicate what is coming to pass. A dancer doesn't just jump from the stage. A backward motion occurs prior to execution of the forward operation. The step backwards is anticipation.

3. Staging

Staging is introducing an idea in

such a way that it is completely and unmistakably obvious. A pose or action

should clearly convey to the viewer the character's posture, mood, reaction or

concept as it relates to the plot line’s narrative and its continuity. Also

helping to tell the tale is the successful use of long, medium, or close-up

shots, as well as camera angles. Do not simultaneously confuse audience with

too many acts. Staging guides the public's attention to the story or idea that

is being revealed. Care must be taken in the background design so that it does

not confuse or interfere with the animation because of the unnecessary detail

behind the animation. Animation and context will work together as a pictorial

unit within a scene.

4. Straight ahead and Pose to Pose

Straight ahead action is so named because an animator actually works straight ahead from the first drawing in the scene. This method typically produces sketches and action that have a new and slightly any look, since the whole held really imaginative. Straight ahead action is used for wild, scrambling actions where spontaneity is important. In pose to pose animation, the animator prepares his action; finding out exactly what sketches would be required to animate the scene. Pose to pose is used for animation that needs good acting, where poses and timing are important. Size, volumes, and proportions are controlled better this way, as is the action.

5. Follow Through and Overlapping Action

Once the main body of the

character stops the other pieces tend to catch up to the main mass of the

character, such as arms, long hair, shoes, coat tails or a dress, fuzzy ears or

a long tail. Nothing stops all at once. It is follow-through. Overlapping

action is when the character changes direction while his clothes or hair

continues forward. The character is going in a new direction, to be followed, a

number of frames later, by his clothes in the new direction. Overlapping

maintains a continually between whole phrases of actions.

6. Slow-out and Slow-in

Slow In and out deals with the

spacing of the in between sketches between the intense poses. As action starts,

we have more drawings near the starting pose, one or two in the middle, and

more drawings near the next pose. Fewer sketches make the action quicker and

more sketches make the action slower. Slow in and slow out soften the play,

making it more lifelike.

7. Arcs

All actions, with few exceptions

(such as the animation of a mechanical device), follow anchor slightly circular

path. This is particularly true of the human form and the behavior of animals.

Arcs give animation a more natural motion and better movement. Both arm motions

head turns and even eye movements are executed on an arcs. Arcs are used widely

in animation, as they produce motion that is more fluid and less static than

movement along a straight line.

8. Secondary Action

A secondary action is an action

that results directly from another action. Secondary acts are important in

heightening interest and adding a realistic complexity to the animation. This

action adds to and enriches the main action and brings more dimensions to the

character animation, supplementing and or enhancing the main action.

9. Timing

Timing, or the pace of an

operation, is an essential concept as it gives meaning to movement. The pace of

an intervention determines how well the concept can be conveyed to the

audience. Timing can also define the weight of an object. Two related artifacts

may appear to be vastly different weights by manipulating timing alone. Timing

may also lead to size and scale of an item or character. Timing plays an

important role in demonstrating the emotional condition of an event or

character. It is the varying speed of the characters movements that indicate

whether a character is lethargic, excited, nervous, or relaxed. Expertise in

timing comes best with experience and personal experimentation, using the trial

and error method in refining technique. The basics are: more sketches between

poses slow and smooth the action. Fewer sketches make the action quicker and

crisper. A combination of slow and quick timing inside a scene adds complexity

and value to the action.

10. Exaggeration

Exaggeration is not severe

exaggeration of a drawing or extremely large, violent action all the time. It¹s

like a caricature of facial features, gestures, poses, attitudes and actions.

Action traced from live action film can be precise, however rigid and mechanical.

For feature animation, a character must travel more loosely to appear

realistic. The same is valid official words, but the action should not be as

large as in a short cartoon style. Exaggeration in a walk or an eye twitch or

even a head turn will give your film more appeal. Use good taste and common

sense to keep from becoming too the atrial and excessively animated.

11. Solid Drawing

The fundamental concepts of

drawing shape, weight, volume solidity and the illusion of 3D relate to

animation as it does to academic drawing. The way you draw cartoons, you draw

in the classical sense, using pencil sketches and drawings for reproduction of

life. You translate these into color and movement giving the characters the

impression of three and four dimensional existence. Three dimensional is

movement in space. The fourth dimension is movement in time.

12. Appeal

Where the live action actor has charm, the animated character has appeal. Audiences like to see a quality of charm, pleasing design, simplicity, communication, or magnetism. A weak drawing or design lacks appeal. A concept that is complex or hard to read lacks appeal. Clumsy forms and clumsy movements both have poor appeal. It doesn't man making everything fluffy and cute but creating a clear visual design that will capture the audience interest.

0 Comments